Screentime is an independent magazine about images and the internet, designed and edited by Ruby Rees-Sheridan and Joseph Cummins.

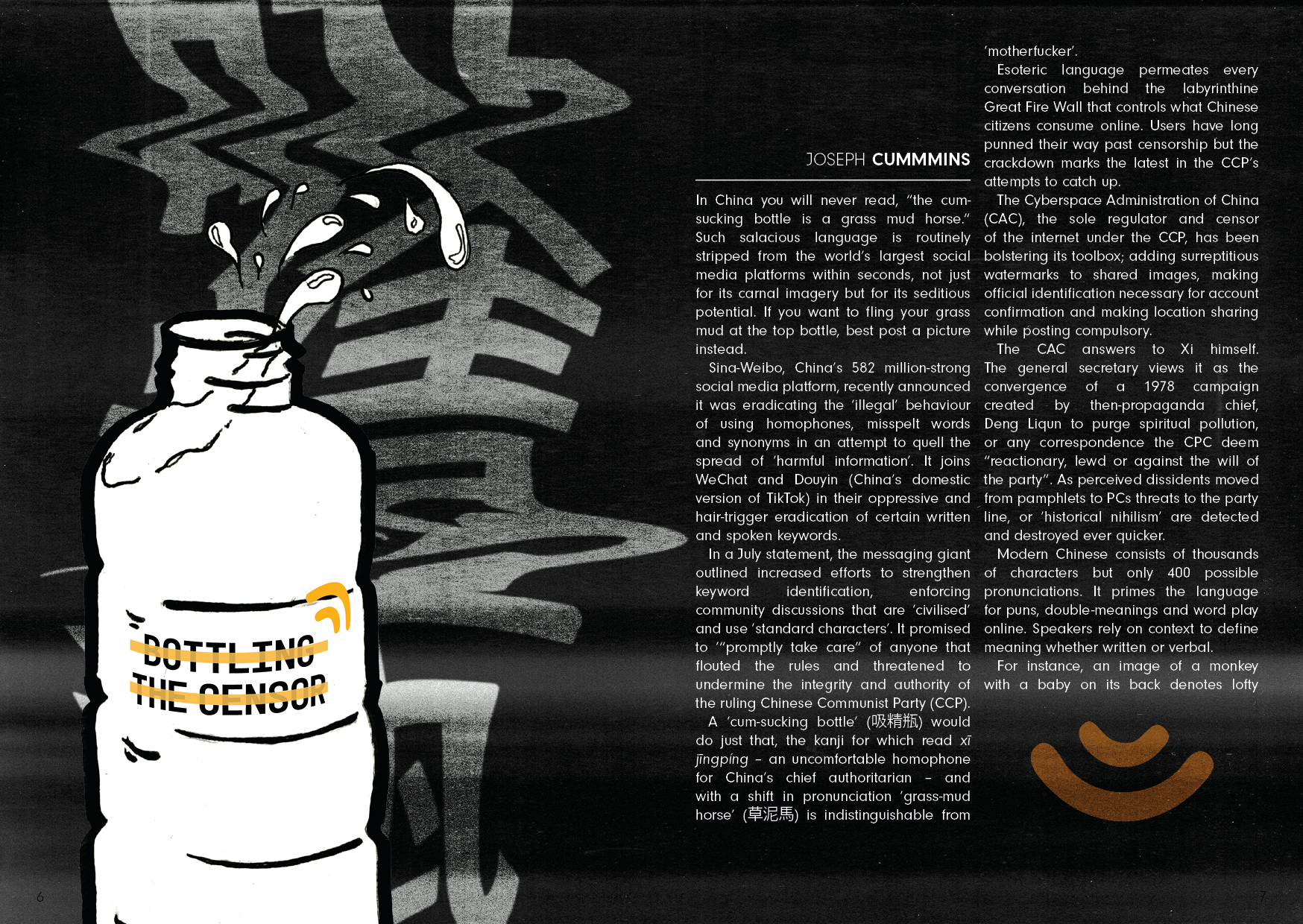

In China you will never read, “the cum-sucking bottle is a grass mud horse.” Such salacious language is routinely stripped from the world’s largest social media platforms within seconds, not just for its carnal imagery but for its seditious potential. If you want to fling your grass mud at the top bottle, best post a picture instead.

Sina-Weibo, China’s 582 million-strong social media platform, recently announced it was eradicating the ‘illegal’ behaviour of using homophones, misspelt words and synonyms in an attempt to quell the spread of ‘harmful information’. It joins WeChat and Douyin (China’s domestic version of TikTok) in their oppressive and hair-trigger eradication of certain written and spoken keywords.

In a July statement, the messaging giant outlined increased efforts to strengthen keyword identification, enforcing community discussions that are ‘civilised’ and use ‘standard characters’. It promised to ‘“promptly take care” of anyone that flouted the rules and threatened to undermine the integrity and authority of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

A ‘cum-sucking bottle’ (吸精瓶) would do just that, the kanji for which read xī jīngpíng – an uncomfortable homophone for China’s chief authoritarian – and with a shift in pronunciation ‘grass-mud horse’ (草泥馬) is indistinguishable from ‘motherfucker’.

Esoteric language permeates every conversation behind the labyrinthine Great Fire Wall that controls what Chinese citizens consume online. Users have long punned their way past censorship but the crackdown marks the latest in the CCP’s attempts to catch up.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the sole regulator and censor of the internet under the CCP, has been bolstering its toolbox; adding surreptitious watermarks to shared images, making official identification necessary for account confirmation and making location sharing while posting compulsory.

The CAC answers to Xi himself. The general secretary views it as the convergence of a 1978 campaign created by then-propaganda chief, Deng Liqun to purge spiritual pollution, or any correspondence the CPC deem “reactionary, lewd or against the will of the party”. As perceived dissidents moved from pamphlets to PCs threats to the party line, or ‘historical nihilism’ are detected and destroyed ever quicker.

Modern Chinese consists of thousands of characters but only 400 possible pronunciations. It primes the language for puns, double-meanings and word play online. Speakers rely on context to define meaning whether written or verbal.

For instance, an image of a monkey with a baby on its back denotes lofty ambitions for newborns as ‘back’ and ‘generations’, and ‘monkey’ and ‘marquis’ are homophones. ‘One cauldron’ (yi ding) is a pun for ‘a certainty’ (yi ding) and bats (fú) are auspicious as the word is a homophone for good fortune.

It is comparable to the equivocal logic of Cockney rhyming slang where simplistic imagery is laced with messages for those in the know and routinely used to dupe those who are not.

It is comparable to the equivocal logic of Cockney rhyming slang where simplistic imagery is laced with messages for those in the know and routinely used to dupe those who are not.

Each year the CCP eradicate content related to the student uprising of 4 June 1989. Any direct written reference, such as indirectly dubbing the anniversary 35 May, never makes it to the platform and a growing selection of images are joining ‘Tank Man’ on the black list.

Depictions of cigarette packets in front of a line of books, a swan sat in the road before an oncoming truck and Francis Goya’s Third of May 1808 have been removed from Weibo and WeChat, all for their allusions to the Tiananmen Square massacre.

But two weeks before the 2017 anniversary the popularity of rice-based spirit Bajiu spiked. Pictures of the bottle appeared in innocuous threads as users evaded the banhammer using the homophones ba and jiu to represent eight and nine.

When Wo Yeshi, China’s own #MeToo movement was quenched within weeks for fear of it stoking democratic sentiments; the words were deftly replaced with ‘rice bunny’, or mi tu in Chinese, and Weibo was soon saturated with pictures of rabbits made from rice.

The scope and variation of the laced imagery means teams tasked with peeling the pictures off the platform rarely succeed before the discourse is beyond their control and only recently has the CAC deployed machine learning algorithms in a bid to catch up.

2017 was a turning point however as Xi unleashed the biggest step up in digital denialism since Tiananmen Square. Following the death of human rights activists-cum-spiritual pollution slinger, Liu Xiabo, the resounding image of his struggle for democracy haunted China’s socials.

Liu was charged with subversion in 2009 – a vague charge used to imprison political opponents in China. While incarcerated he was awarded the Nobel peace prize and in deference to his efforts, his medal was presented to an empty seat.

The vacated chair became and anti-government symbol. The CCP feared disenfranchised citizens would mobilise around the images, scrubbing public posts immediately. And, in an unprecedented move, images exchanged in private correspondence became targets for the censor.

Any photo containing an empty chair was purged, along with screengrabs of other conversations, official government documentation and the candle emoji. Senders can not tell their messages were being censored, with the recipient simply told: “this content is illegal!”.

CitizenLab research led by Lotus Ruan exposed the limitations of the current standard of automated censorship for directly political imagery. Mirroring, rotating and manipulating dimensions all dissuade the filter, and one user successfully shared a shot from the 2019 Hong Kong protests by adding brush strokes.

Ruan explained that the tool lacks holistic semantic understanding of the images it filters so moving a few key pixels or adding a confusing white border can be enough to sneak an image through.

However as the censors squeeze and machine learning’s capability to distinguish politically charged imagery increases, it is the Chinese language’s ancient use of symbolism that will facilitate true conversations online.

However as the censors squeeze and machine learning’s capability to distinguish politically charged imagery increases, it is the Chinese language’s ancient use of symbolism that will facilitate true conversations online.

As you read this, each subversive image referenced is inevitably defunct – if your writer knows about them so does the CAC. Despite wielding the most advanced network of censorship currently possible however, the CAC is routinely bested.

That social media giants are interwoven with the CCP makes them dangerous to subvert but Xi’s critics are driven by a need to communicate openly. Fuelled by an ever-evolving visual language, they are transforming symbols like the mud-horse, rice-bunny and cum-bottle into martyrs.