Anime is obsessive and leering in its detail. Even as the medium has woken up from a stupor of misogynism and objectification, one trope still hangs over every almost scene. And it’s not physiologically impossible bodies – although this still is seen far too often – it’s power lines that are uncomfortably prevalent.

Defined by details, anime is as much about stark, colourful images, taught metropolises and midnight ramen as it is about the narrative. So much so that there are now over 5000 Instagram accounts devoted to teasing the pause button and plucking out the best frames.

Under such scrutiny, and when setting is a crucial character, not an inch of screen can be wasted. So why would an animator, delirious with deadlines, give so much of their canvas to stringing up power lines and infrastructure?

By 1995, the bubble of the Japanese economic miracle had burst. As the faith in the techno-utopianism that had fuelled the economic growth receded, the sheen started to peel from sci-fi anime too. The cities of Metropolis, One Punch Man and a whole raft of anime mirror a modern Tokyo of high-rise, low space and endless wiring.

Neon Genesis: Evangelion – a hard-wired classic of the genre

Neon Genesis: Evangelion was the first true rendition of Tokyo’s tendency to build first and then bolt the planning on after. Tokyo-3, the city setting of the series (Tokyo-1 and 2 didn’t make it to the first episode) is a nest of new and old, tied up in cabling.

It’s also an urban sprawl on high alert for the inevitable attack of tsunami-sized ‘angels’ seeking to destroy it. They come from the sea, the depths of the earth or from whipped up air to wreak destruction.

While the overarching metaphor of the series is evangelical, the fate of Tokyo-1 and Tokyo-2 was no doubt more elemental. Like life in the real Tokyo, heating up instant ramen and using cramped public transport all play out in the shadow of a hulking natural disaster. Neon Genesis was the first time the city itself solely bore the existential threat.

The scars of previous battles rend the streets and workers fettle with repairs in the background. And when the action ramps up again, power lines, those fragile yet fundamental filaments, are the first to go.

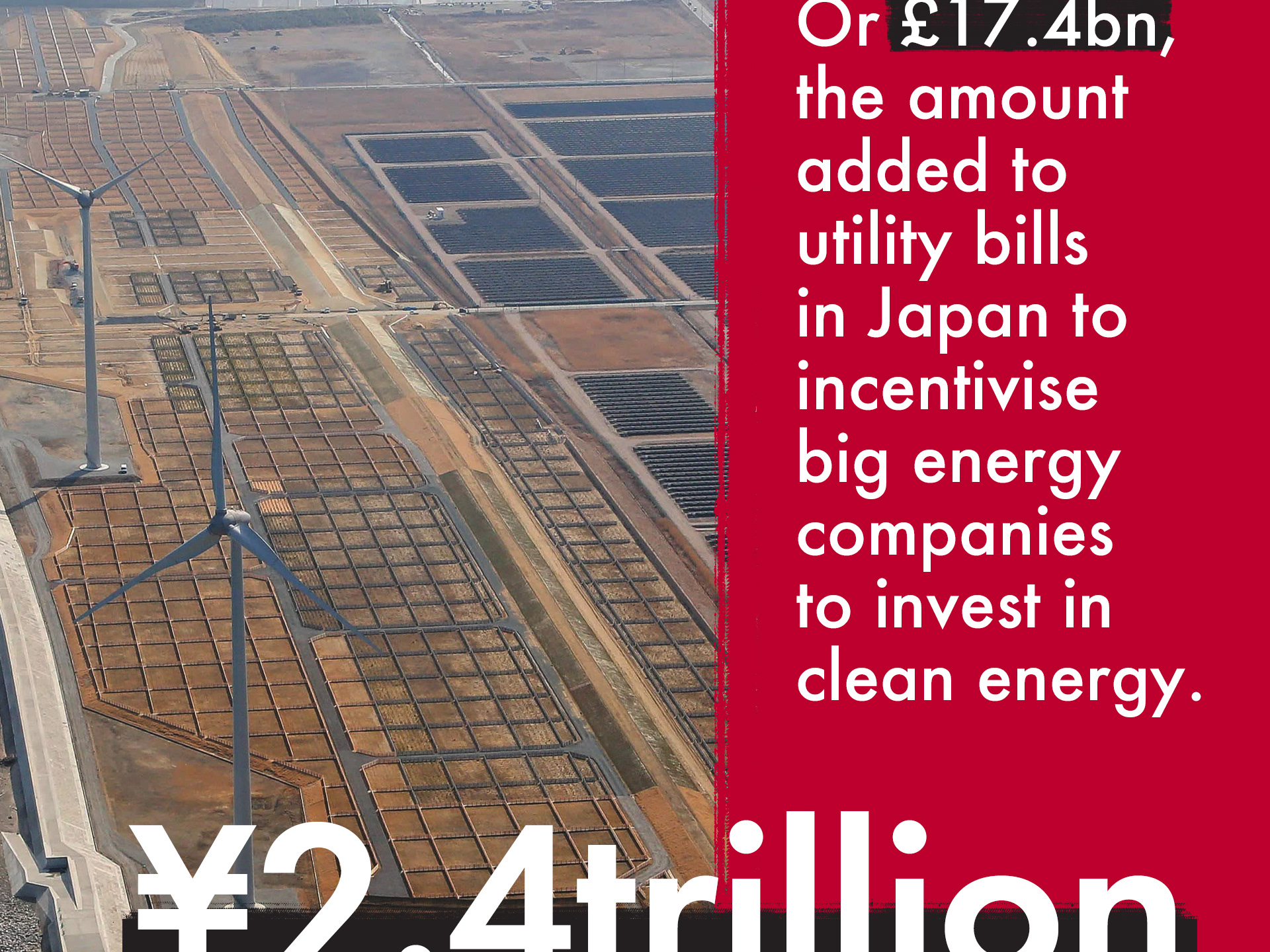

As Japan’s post-war economy exploded, city planners struggled to keep up. They were forced to build quickly – considering infrastructure first, humans second.

Central to this was the power network. The 50s saw the single largest expansion of an overhead power grid anywhere on earth, fuelled by governmental pressure and Tokyo Electric Power Company’s (TEPCO) firm assertion that overhead lines were quicker to build and much safer.

TEPCO said: “In the events of flooding or landslides, it’s harder to isolate damaged areas of a subterranean system,” the company points out, “The amount of time necessary to restore power to damaged areas [is greatly increased].”

It was all the justification the Japanese Diet needed to feed their hunger for expansion. But, by the 1990s, independent analysis from NPO (non pole community) proved this assertion wildly incorrect, by which time all but two of Tokyo’s 27 wards were solely reliant on power lines.

Burning and collapsed buildings after the Hanshin earthquake in 1995– Britannia

More than 6000 people where killed when the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake tore through Kobe. Falling power lines and exposed electric infrastructure hindered emergency workers, leaving parts of the country without aid as well as power.

As the shock of the disaster turned to fury at governmental failings, Toshikazu Inoue, secretary of NPO showed that the national spend on replacing fallen lines and repairing damage was five times that of installing the same lines underground.

It’s this sudden anxiety toward rapid expansion and dependence on something so flimsy that has given power lines such prominence in Japanese culture. The technological utopianism of the early 60s has faded to unease as the tech bubble started to wane in the 1990s.

Hideaki Anno, creator of Evangelion, was obsessed with the mechanical structure behind the gloss of modern Japan when he created Neon Genesis in 1995.

“I want to draw buildings, electricity poles, highways, and whatever man built with concrete and steel,” says Anno, “I made sure to depict them authentically, perhaps with exaggeration but without lying.”

Man is susceptible to failure in Anno’s work. Where previously anime mechs (huge anthropomorphised robots) are powered by “clean nuclear reactors, powered by Jupiter-mined helium”, the mechs of Evangelion are quite literally plugged in at the mains.

There is even an episode dedicated to Tokyo’s response to a threat when, quite literally, powerless. The result is taught and angsty – a mess of bureaucratic finger pointing. Rarely has anime been so true to life as Anno unveils Japan’s disillusionment with technology’s magic bullet.

"No matter where you go, everyone’s connected.”

–Serial Experiments Lain.

Now, as the wires that lace the streets connect us not just with electricity but information, their presence on screen betrays a fear of something more sinister and unknowable than natural disaster.

Serial Experiments Lain, released just three years after Neon Genesis, was Promethean. The power lines on screen connect pools of shadow that fizz with threat. And the narrative of a girl losing herself to the internet strays ever closer to them. The series culminates in ‘the wired’ straying beyond the digital and manifesting as a physical monstrosity. All set in the confines a cookie-cutter Japanese bedroom.

What lies in the shadows – Serial Experiments Lain

Japan is by far the most welcoming nation to robotic dominance – they are three times more comfortable with a robot in the home than the UK. But when it comes to software – the ghost in the shell – Japan has been uncharacteristically slow on the uptake.

None of the of the world’s 15 largest AI companies in the world are Japanese and despite being the largest exporter of technology per capita, only 3% of this is AI. Despite concerted advice to stay away, the threat of the Wired in Serial Experiments Lain grows as its main character falls further into it.

Hyper-connectivity drives a man to suicide and the voices of deceased school children start to resurface online. This all plays out as the shadows, bristling with HAL-3000-esque red dots, close around the characters’ world. And the artist reminds us that this threat has a mainline directly to us – the mass of cabling we’re so readily connecting ourselves to.

From the lessons of Genesis and Serial Experiments Lain it will not be long before we allow ourselves to slide into a co-dependence with the wires we rely on. But just as anime has accelerated us towards a cyborg future, it shows Japan’s unease with the prospect of second billing when we get there.